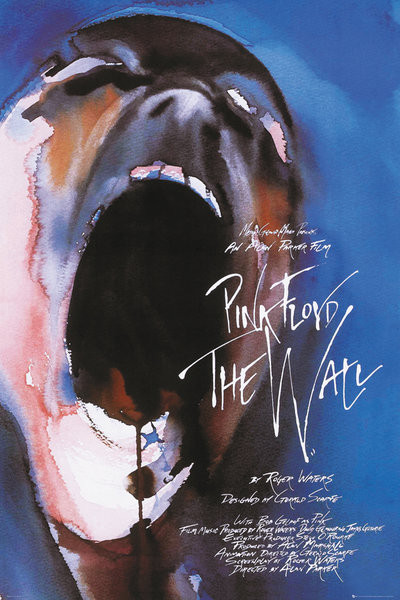

At its core, the theme and title of this blog, 'Practical Solipsism', lies what I believe to be the essence of what I still hold to be the perhaps most genuine and telling piece of narrative art of the 20th century, namely Pink Floyd's 'The Wall'. While the first post actually made onto the blog might be read as a 'warning' of what is to come, a sort of announcement of the content of the blog to come, my treatment of The Wall is still what makes out the heart and soul of the blog, of my writing, of my thinking. Truth be told, I think I have made only very few posts which could not, in some way, be made to make sense through a close reading (or listening-to) of The Wall. In some sense, I think The Wall is what I term 'Practical Solipsism' - the 'Urbild', so to speak, of the latter. At much the same time, I imagine there's hardly anyone familiar the work of D. F. Wallace who wouldn't also recognise his impact on this blog, on my writing, on my thinking. As much as Wallace might've liked to see himself as 'beyond' the Post and the Modern, his work remains deeply interreferential. The title of his 1992 essay 'E Unibus Pluram' is mentioned twice in the 1996 novel 'Infinite Jest', yet both concern exactly the same topic as this blog, what I have termed 'Practical Solipsism' and Wallace, in Infinite Jest, speaks of as a sort of 'Existential Individuality':

'We're all on each other's food chain. All of us. It's an individual sport. Welcome to the meaning of individual. We're each deeply alone here. It's what we all have in common, this aloneness.'

'E Unibus Pluram,' Ingersoll muses.

Hal looks from face to face. Ingersoll's face is completely devoid of eyebrows and is round and dustily freckled, not unlike a Mrs. Clarke pancake. 'So how can we also be together? How can we be friends? How can Ingersoll root for Arslanian in Idris's singles at the Port Washington thing when if Idris loses Ingersoll gets to challenge for his spot again?'

'I do not require his root, for I am ready.' Arslanian bares canines.

'Well that's the whole point. How can we be friends? Even if we all live and eat and shower and play together, how can we keep from being 136 deeply alone people all jammed together?'

'You're talking about community. This is a community-spiel.'

'I think alienation,' Arslanian says, rolling the profile over to signify he's talking to Ingersoll. 'Existential individuality, frequently referred to in the West. Solipsism.' His upper lip goes up and down over his teeth.

Hal says, 'In a nutshell, what we're talking about here is loneliness.'

(Wallace 1996: 112-113)

Shortly after where I left the quote, the boys, following Hal's suggestion, conclude that really, it is suffering which unites them, a common enemy, that the poor treatment they receive from their coaches is actually a gift - that it is their medicine. Except of course that that cannot possibly be the case, considering what happens in the next roughly 900 pages of the book. Wallace, I think, rejects his own solution, defaulting back to the first thesis put forth by Hal - that what unites them is their absolute loneliness. A notion made only worse, more pessimistic, when considering the content of E Unibus Pluram itself, which to be appears nothing short of a treatise on loneliness as such, but hence also the very being of Practical Solipsism:

[L]onely people are usually lonely not because of hideous deformity or odor or obnoxiousness—in fact there exist today support- and social groups for persons with precisely these attributes. Lonely people tend, rather, to be lonely because they decline to bear the psychic costs of being around other humans. They are allergic to people. People affect them too strongly. Let’s call the average U.S. lonely person Joe Briefcase. Joe Briefcase fears and loathes the strain of the special self-consciousness which seems to afflict him only when other real human beings are around, staring, their human sense-antennae abristle. Joe B. fears how he might appear, come across, to watchers. He chooses to sit out the enormously stressful U.S. game of appearance poker.

(Wallace 1997: 23)

And here, too, the connection to Solipsism is made - rather clearly, even if adverbially:

If it’s true that many Americans are lonely, and if it’s true that many lonely people are prodigious TV-watchers, and it’s true that lonely people find in television’s 2-D images relief from their stressful reluctance to be around real human beings, then it’s also obvious that the more time spent at home alone watching TV, the less time spent in the world of real human beings, and that the less time spent in the real human world, the harder it becomes not to feel inadequate to the tasks involved in being a part of the world, thus fundamentally apart from it, alienated from it, solipsistic, lonely.

(Wallace 1997: 38)

It is in this last quote that I think the notion not of a 'theoretical' but a 'practical' solipsism is most clearly expressed in the work of Wallace, or perhaps I ought to say it is rather where it is put most concisely rather than most clearly - Infinite Jest as a whole seems more or less the clearest literary depiction of the phenomenon I could possibly imagine. But that doesn't mean that Wallace managed to say everything, or even half of what was to be said.

At some further point in time I'd like to return both to Infinite Jest and E Unibus Pluram, especially that last excerpt. But at the same time, my own enquiry into the nature of solipsism didn't begin there but with Pink Floyd and their Wall. And so it seems fitting to be that the new undertaking of a hermeneutic of solipsism begins exactly there, with a hermeneutic of the Wall at once as a poignant metaphor for the nature of solipsism at all, but also as an outstanding, now in the sense of the album itself, display both of a post-modern consciousness and an awareness of the shortcomings of postmodernity. In a very real sense, the connection which I am attempting, even if with baby steps, between the literary world of Wallace and the music and poetry of Pink Floyd, is a connection which I think goes beyond theme, but also shares a deeper literary genre-awareness, namely as examples of what Wallace himself would've referred to as 'Sincerity', or, in other words, actual metamodernity.

My philosophical influences may remain, throughout this project, more or less clear. Yet there will be times where I think it is relevant at the very least to make polite reference to those who came before me. And so that seems a fitting place to start, in considering how in the world we are to get started.

Das Entscheidende ist nicht, aus dem Zirkel heraus-, sondern in ihn nach der rechten Weise hineinzukommen

(Heidegger 1967: 153)

There seems to be a very real problem as to what the beginning of any hermeneutic undertaking is concerned, namely the very beginning itself. And while I think that the hermeneutic-phenomenological heuristic (or maxim) 'zu den Sachen selbst!' gives an appropriate sense of what we are to do - namely concern ourselves with the content of our hermeneutic enterprise in a very direct sense, it also assumes that we know what this "Sache", this thing, is. And I don't think that's clear at all.

On the one hand, we're concerned with The Wall, and The Wall is our Sache. Inasmuch then as we desire to go to "the thing itself", it seems to me that we face the problem of being required to know what The Wall is before we can even begin our enquiry as to what The Wall is. It boils down, I think, to a decision. At some point in time we must determine, simply by means of determination, where The Wall begins (and where it ends, insofar as the two, and I do believe this to be the case, necessarily coincide). The question thus becomes whether we have any reason to believe that one "beginning" might be more apt to choose than the other, but this consideration would have to rely on The Wall, which we as yet hold to be unknown to us.

The issue of the beginning of a hermeneutic of The Wall is solved most plausibly by reference to something which I have previously expressed that I think is all too often overlooked, namely the necessary occasionality of art. In considering The Wall in the sense of its own aisthesis and its own phenomenon, we have to consider how it "greets" us, how it "meets" us, what it tells us about itself. No undertaking or process (Vollzug) of understanding can ever be accomplished without some degree of prejudice of the matter at hand, and while Gadamer might be wring in that this includes the prejudice of the absolute truth of the account received, in this case that's not enough, as we first have to find out what the account even consists of.

Yet I do think that The Wall gives us a reason to establish some expectations more than others, and these are exactly those set by our meeting it and facing it in its occasionality. In a digital age, the materiality of The Wall might well be forgotten, but this is a sign of our times, not something which relates to The Wall itself. And so I will not claim that those prejudices which I am about to give an account of are necessarily the only ones with which an appropriate understanding of The Wall might be delivered. I will, however, claim that they are apt. Consider the following.

Whereas the music of the 19th centuries and before might've been dissipated largely by sheet music or other means, the dawn of the recording industry in the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th necessarily changed the circumstances of the mimetic structure of music. The relation between an "original" and its reproduction following the widespread distributed of pre-recorded and pre-performed music is fundamentally different from the preceding mimetic structure. It is, I believe, much easier to conceive of an "abstract" piece of music which emanates in its every performance if that piece of music was written before the dawn of the recording industry, meaning that there could be no standard to it aside from its own compositional structure. The fact that Pink Floyd's music was recorded and distributed as recorded music, and that humanity did and will receive their music largely as recorded rather than as performed, means that the recording carries the appearance of an authority which surely, it seems to me, we have not yet dared to challenge. The fact that there are cover bands of Pink Floyd seems to me to be the paramount example of a mimetic structure which doesn't see itself in the light of emanation; somehow, something is lost once the voice of authenticity is recognised as real, rather than approaching The Wall and the other music of Pink Floyd as but one performance of an artwork which might be performed in a multitude of ways. Perhaps, as time passes, things will change, as it to some extent has within the world of Jazz, but I sincerely doubt that we'll see any change within the decades to come. Nevertheless, the fact that music was distributed in the way it was, namely by vinyl records (at least in cases where you wanted to hear the whole of The Wall, which is what we're concerned with), means that the distribution itself might be able to provide us with a source of "apt prejudices" for The Wall. And I do think that this is the case. See, in receiving The Wall, you were never simply faced with a black record in a clear packaging - and if it were so, then we'd have known simply to listen to the record from one end to the other and that'd be that, but instead with a carefully designed guide to what was to come.

The Wall, in its material sense now, depicts a white brick wall with a light blue-grey morter (the album title and band name present as a sticker to be removed), which of course provides the first apt prejudice concerning The Wall, namely the presence of a wall. Banal as the point may seem, I think it carries serious weight - on listening to and attempting to The Wall, you are, in a very serious sense, attempting to make sense of The Wall, not simply songs and sounds, music and voices. The matter of fact is that the whole of what is to come has to be undertood within these confines, as somehow having to do with "a wall". When the time comes to consider the first track off the album, "In The Flesh?", I think the necessity of the presupposition of some "Wall" to made sense of will become clear as day - further, the track itself seems to even know this fact, and confronts it directly. But all in good time.

The Double-LP opened up shows the "other" side of the Wall, featuring cartoon figures and grafitti-like credits for the album. The cartoons are, especially in the light of the later film version of The Wall, highly relevant to the album, but in ways that I think will likely best make sense to treat once the album itself has been made sense of sonically - for the time being, I think it should suffice to say that the cartoons are wildly mad and surreal to look at, perhaps even somewhat horrifying and disturbed. We are, I think might aptly be conjectured, not in for a "good time".

On removing the vinyl records of the double-LP, you are met by a custom white-brick sleeve naming both the side of the album (sides 1, 2, 3 and 4) and the tracks which belong to every side, including their lyrics, written in a cursive handwriting. This, I believe, is where the true "meat" is provided as to what our expectations and prejudices are concerned. Pink Floyd very plainly spells out what is to happen, and there is a certain material aspect here which is too easily forgotten when the album is streamed, namely that there are literal temporal gaps between the four sides. The album, I think, gives us an initial reason to believe that it has some sort of structure. Not only that The Wall is a coherent entity - manifest in the ever-presence of the white bricks on both cover and sleeves, but that it has a fourfold structure.

The fact that this fourfold is a case of genuine structure rather than pure conjecture is seen when considering the very tracklists themselves. As with so many other artworks, while dangerous, I think it worthwhile to sometimes consider how the lack of a certain feature would change our approach to the artwork. Consider thus how the album might've been experienced if no track lists were provided - and suddenly the album would look rather different. Whilst unknown to those who've not yet heard the record, many tracks on the album blend together in such a way that you really wouldn't have known that they were different tracks if not for streaming clearly dividing the tracks for you. On hearing the album in its physical form, as a vinyl record, those lines become particularly blurry. The track names and their being provided is not mere accident, but instead provides real context for understanding The Wall itself. The question thus becomes how this ties into possibly understanding the fourfold structure has more than merely physical.

While we might be used to hearing of a three-arch structure, what the track-list of The Wall provides us with is a four-arch structure, arches marked very clearly by the physical constraints of The Wall in its materiality and the track names of those musical performances which make up those four sides. While some parts will only make sense once the tracks have been heard, much can be said from the names themselves:

Side 1:

In The Flesh?

The Thin Ice

Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1

The Happiest Days of Our Lives

Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2

Mother

Side 2:

Goodbye Blue Sky

Empty Spaces

Young Lust

One of My Turns

Don't Leave Me Now

Another Brick in the Wall, Part 3

Goodbye Cruel World

Side 3:

Hey You

Is There Anybody Out There?

Nobody Home

Vera

Bring the Boys Back Home

Comfortably Numb

Side 4:

The Show Must Go On

In the Flesh

Run Like Hell

Waiting for the Worms

Stop

The Trial

Outside the Wall

What I believe to be present and visible in the tracklist is the structure of The Wall as an essentially dialogical artwork, taking on the structure of some sort of "conversation", of "question" and "answer" - or perhaps "response". Take the first track off the album, "In The Flesh?", posing a question to be answered, seemingly, on side 4 with "In The Flesh" - the album tells us of its own coherence, that things make sense, that it is a whole, not just by having a name (The Wall) and having that "iconography" be ever-present in the physical album, but also by tying together sides 1 and 4 by this question-response-structure. While it is difficult to establish from names alone in which sense side 1 is a coherent and dialogical entity, it must nevertheless always stand as something which belongs before the intuitively coherent side 2 and its mirror structure, beginning with "Goodbye Blue Sky" and ending with "Goodbye Cruel World". Side 3, much the same, shows a further dialectical-dialogical structure in its first three tracks, "Hey You" - "Is There Anybody Out There?" - "Nobody Home". And, of course, there are the countless mentions of The Wall - present both on sides 1, 2 and 4.

The concrete evidence that The Wall does in fact have a four-arch structure can only be concluded once the album has been heard and understood - for now, the point was much more to say that I think we are well within reason to expect at once coherence throughout The Wall as an overarching album, highlighted by the connection between sides 1 and 4, but also that the sides are at the very least capable of being somewhat self-contained, as seen on side 2. How the sides relate to themselves and to each other is a task which will be undertaken once they have been understood on their terms, a task which still lies in the future.

Last of all, I wish briefly to comment on the importance of the presence of the official lyrics, or rather, why I will not yet comment on them. Because, as things will have it, not every word spoken on the record turns out to be present on the sleeves. The importance of this fact, however, will only make sense once we have undertaken the next step of our hermeneutic enquiry, which will be the first song off The Wall, "In The Flesh?".