Life will be televised. Whose?

I.

The recent history of stage art in as understood through classical drama and theatre fits all too beautifully into the mythological schemata of civilisational decline and social alienation so readily available and present in most critiques of modernity.

At the beginning of the 20th century, while theatre was still the chief mode of (more or less) narrative, staged art, a medium which, at its core, both respects its own occasionality and pays its dues to social reality as a key meeting of people. The play, staged as it may be, essentially retains little ideal of genuine authenticity, having to be re-staged for literal different stages, but also for different actors and audiences. But the play, staged and performed at select and limited times only, must be understood as occasional in that very sense too - that a play is an occasion, one in which many people gather, and you, if you wish to see it, must show up alongside not just the other onlookers, but one in which you are fundamentally dependent on the appearance and work of those who are setting the play. The play, so understood, is and must be an inherently highly social event.

The dawn of cinema changed things, even if only a little at first. Within the theatre itself, conceived now as the very physical building and not the art form, the age-old division between the house and the stage as a divide between audience and performers is essentially dissolved. Which is not to say that there aren't still many people hard at work to make the whole show come together. The period of cinema before the introduction of the talkie where music may be performed alongside the film only makes this all the clearer, for which reason the introduction of the talkie can hardly be overlooked either - what exactly happened, I think, is difficult to tell, but it seems clear that the cinema before and after said event are as incredibly different as to essentially appear to be two different art forms. But what even the presence of live musicians cannot deny is that the fact that real, live people were no longer the intended point of attention of a performance. Where an audience (consisting of people) had previously gathered for the occasion of a cast and crew (consisting of people) performing a particular performance, the latter part of the equation had been cut out.

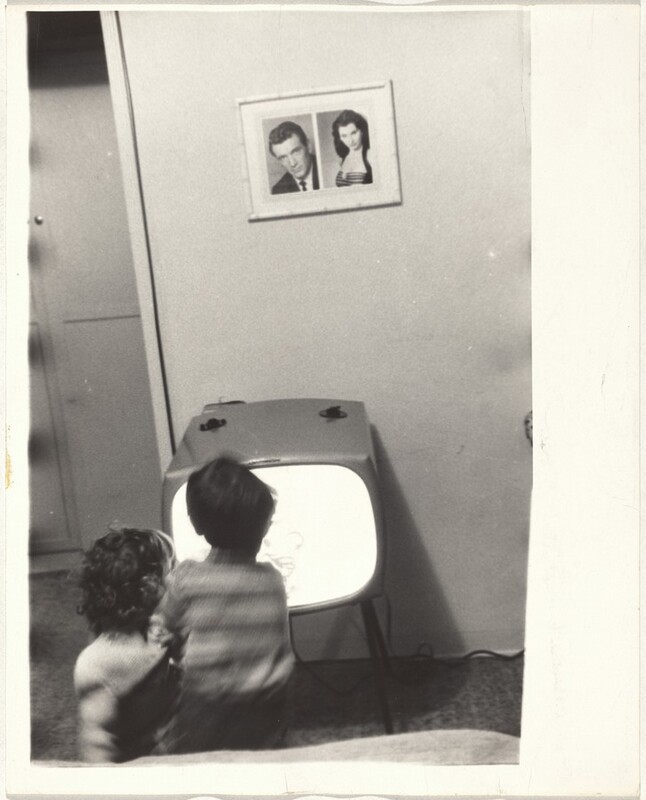

The introduction of the TV-set further complicated things, but the itself still doesn't quite get rid of its socially constructive function as a means of giving a cohesive foundation for interaction and discourse. The fact that in the past, TV could serve as an actual, general and consistent topic for water-cooler talk is a direct testament to this function. And while a certain degree of occasionality was maintained, the introduction of the TV-set marks the first step in what would become an ultimative reduction of the house of the theatre, of the audience. As much as it might have been the same TV-show we saw last night, the degree or mode of sameness is nevertheless changed - if in nothing else, then in the fact that I am now left to ponder over it myself, right there in my chair or sofa or other piece of preferred TV-watching furniture. The extent to which American Post-Modern fiction has managed to depict the centrality of the TV-set to modern life is, I think, a genuine literary feat, and not one to be scuffed at. As the amount of channels and their respective air-times expanded, though, TV changed, fundamentally. There's a world of a difference between having or not having seen the single TV-show that was on last night, and then having seen one but not any of the simultaneous 20 running on other channels. Matter of fact is that the latter is essentially a sign of the genuine eradication of large-scale or even significant occasionality to the movie-watching experience - or, at the very least, to movie-watching consciousness, a consciousness beginning here to become not just less public but more private. The TV-set introduces a new level of internality to the experience of watching a film, you're there with yourself and your family. That is, until the family is gotten rid of.

The 21st century has seen the rise of streaming platforms. If streaming were only a matter of choosing what was on TV, that'd be one thing, and surely it would be enough to highlight the continuation of the development I've tried to sketch in the above paragraph. But that's not how things went; the physicality of visual media consumption changed too. It is, by and large, no coincidence that media consumption now takes place on and is tailored to screens which are literally not physically large enough to be suitable for co-viewing. Where one might well focus on the way in which algorithmic media consumption is inherently different due to its personalised nature, and indeed one would be right to do so, doing so without first taking into account the physical backdrop which made this possible would be to miss the forest for the trees. The advent of personalised content algorithms only makes sense in a world where personal media consumption is already present: the algorithmic media loop is directly dependent on our media consumption already being individual and socially alienated. To repeat the point as to make it overtly obvious, it is hardly the case that personalised algorithms were just so good that we had to start watching TV on our phones instead of the actual television. Which means that the house has now been finally reduced. In consuming media, there is no longer anything but consumption, and an individual consumption at that. The idea of generality in media seen can only be established by the streaming platform showing either an amount of likes (as is the case of social media) or belonging to a "Top-10" (or similar) on a streaming platform. But these are inherently external to the nature of the content itself ; an instagram reel is not created to be liked by 200 thousand viewers, that fact is accidental, much the same as no Netflix-programme can be expected to actually reach the top 10 until it does, at which point following seasons are likely to follow troop (if nothing else, I think, for the fact that anything that has already entered the top 10 becomes socially relevant enough to warrant an automatic viewing upon the release of a new season by a large amount of people).

II.

The question which remains is why this matters to us, on an individual level. Surely, we might say, consuming hours upon hours of television, reels or YouTube videos per day can't be healthy. But that's beside the point - there's a reason the reduction of the sociality of media consumption has been my primary focus. And here's the point, one which can be made more readily now than ever before: If it's real, it's on TV. In a literal sense of the term, what appears on TV (and its successors) takes on the status of fact, of deed, of performance, of happening - factuality itself is constituted in and through TV. It is no coincidence that the narcissistic tendency of the current age which sees portrayals of the likes of love on TV as "more real than reality itself" see it just that way. The very literal linguistic and social schemata which are reflected in and even constitute social reality are acquired and inherited now through media consumption, not through social reality itself. The criteria of reality previously internal to reality itself has been made manifestly external: Pics or it didn't happen. By Sellars' conception, contemporary philosophy is faced with two projections, respectively the Manifest Image of Man and the Scientific Image of Man, forced now to determine which is real. What he thus neglects to notice is the nature of the projection itself - namely as the very real means by which reality shows itself as reality .

So we take pictures, and we televise our own lives. But why? And who's watching, anyway?

I think the analysis that people post on Instagram in order to somehow boost their self-image or that they do it to project an image of themselves into reality is faulty. The relation is the exact other way around: The image on Instagram claims to be more real than reality, and the real "you" posting on Instagram is all the less real for it. Again: pics or it didn't happen.

The question essentially boils down to one of identity, of who we are as people, persons, individuals. And, in truth, I think it boils down to something surprisingly simple: narratives, relationships and the intersection between the two. And when I say that identity is thus fundamentally narrative, the point is of course a twofold one.

All too often questions of identity are understood wrongly exactly because they aren't understood as questions, and if they're understood as questions, I'm most often asking myself. If instead I turn around and ask you a question concerning your identity, namely who you are, that your response must and will always consist in you telling me. This is the first sense in which identity is fundamentally narrative: identity is something which is told. The answer itself, however, must also take a certain format. True as it may be that I may, being asked who I am, describe myself simply by terms of what I am doing, the matter of fact is that these doings can only be understood on the individuated level once they are considered within the context and confines of a life lived throughout time, told now as a story. This is the second sense in which identity is fundamentally narrative.

Part II soon.